Books

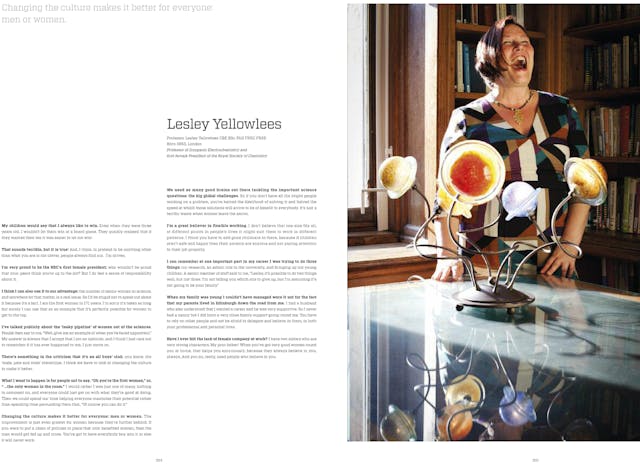

100 Leading Ladies

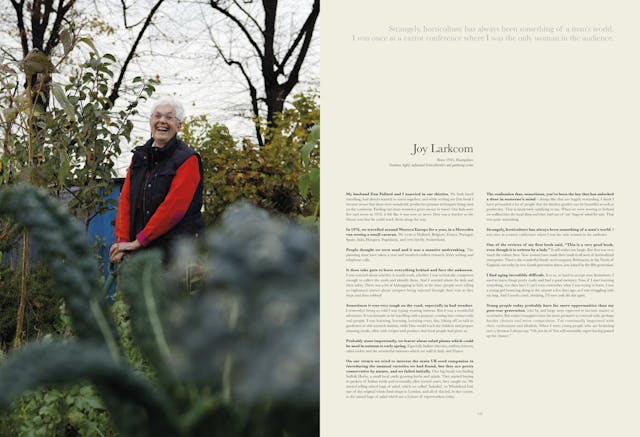

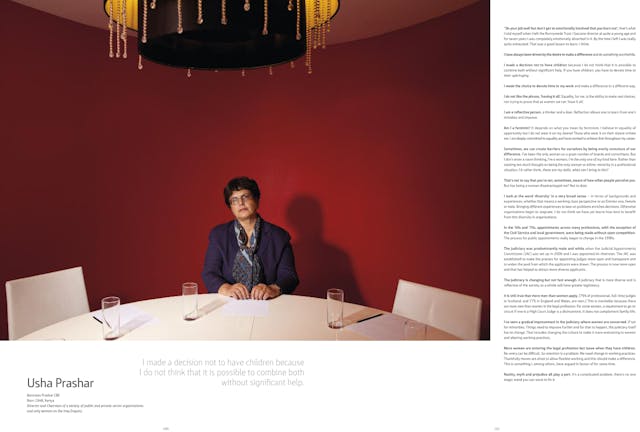

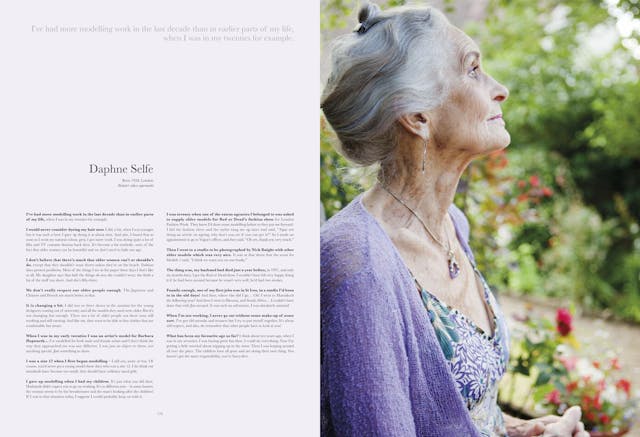

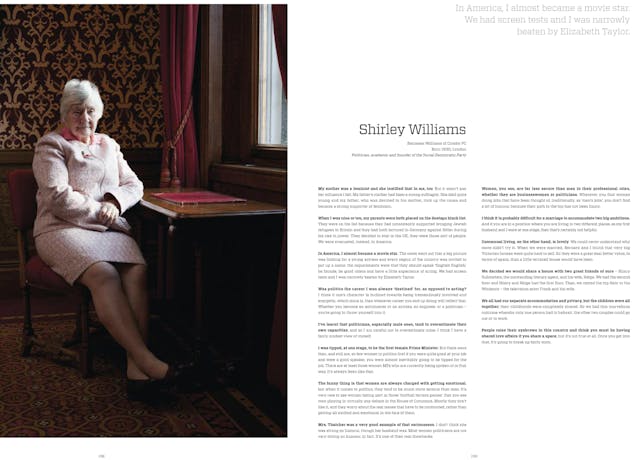

The 100 British senior women, over 55, photographed and interviewed for this timely work helped transform the perception of what is possible for women to achieve in their lives.

One hundred women, one hundred portraits, one hundred unique stories that shine a guiding light on the paths they took to success in their fields and in life, so that younger women can also find their way.

- Publisher:

- Dewi Lewis Media, UK

- Published:

- 2014

Sample Book Pages

Please also visit - www.100leadingladies.com - for more information about this project.

Harriet Minter’s introductory text originally published in the book - 100 Leading Ladies as well as in The Guardian in September 2014.

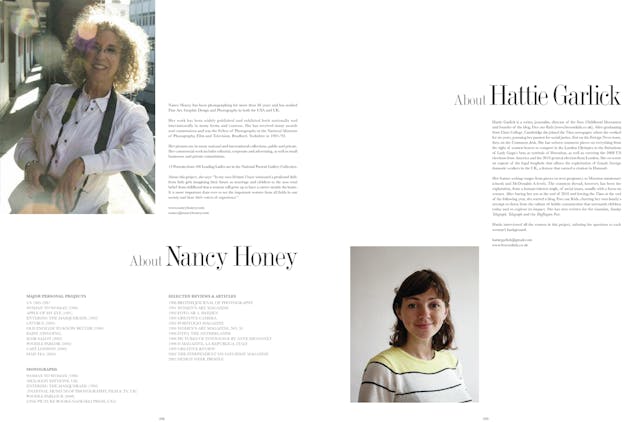

The first time I meet Nancy Honey she’s surrounded by packing boxes and bubble wrap. She’s on the move from her house in south London to a flat in the heart of the City, downsizing and questioning what she’ll be able to fit into her new home. She hops around the kitchen, making tea and finding biscuits, all the while chatting about the grand passion that has taken over her life in the last few years. A passion so strong that she’s selling her house to fund it.

It’s been two years since the photographer started on her latest project, 100 Leading Ladies – a series of portraits and interviews with some of the most successful women in the UK. In that time she’s found, researched, photographed and interviewed (with the journalist, Hattie Garlick) 100 senior women with the aim of turning the portraits into a book and exhibition. She’s also funded the whole project herself, with the result that she’s been forced to sell her house. For anyone else this might have taken the shine off the project, but Honey seems unfazed by it.

“There seems to be a defining characteristic of success,” she says, “which is the ability to be optimistic when things are going wrong. Also to reinvent yourself, which I think women are very good at. All the interviews in Leading Ladies have shown me how many women have had to do that.”

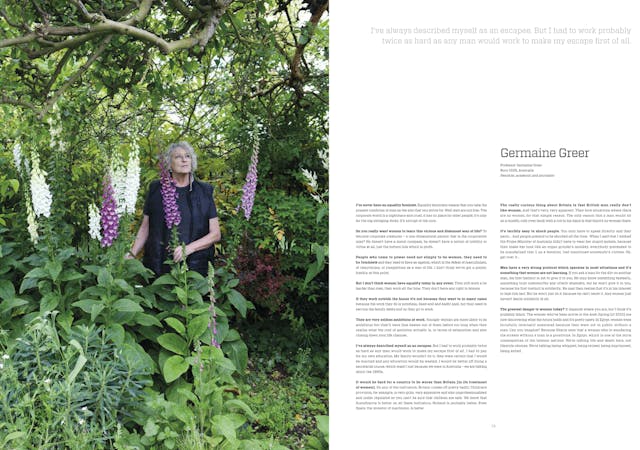

The women she’s interviewed range from Germaine Greer to Baroness Scotland, and cover every area in between. This was deliberate.

“There were certain guidelines that I’d set up for myself, because it’s always nice to give yourself a brief and within those guidelines was, ‘every walk of life’. So if I wasn’t able to find someone from a walk of life that I thought was important to cover I would be determined to keep searching.”

A lesser person might have scaled down the project, aimed for 50 or even just 10 but Honey had a goal and seems to never have wavered in her belief that she would hit it. One thing that both helped and surprised her was how willing the women involved were to help her.

“Helena Kennedy was a great example of this. I photographed her first about two years ago and after she sat down, got out her phone and said, ‘Okay, here are some of my friends and here’s their contact details and I’m sure they’d be happy to do it’. I just couldn’t believe it, I thought this is going to help a lot.”

“So that’s probably how, between those and the others that I knew I could contact, by two or three months in I had 14. Compared to 100 it’s nothing but then each of those 14 would suggest people. Sometimes it would be someone they knew so they’d pass on their contact details and say I could mention them but sometimes it was just a suggestion, a ‘Have you ever heard of so and so?’.”

“That was a part of the project that I absolutely loved because another of my main reasons for doing it was to discover these powerful, strong, amazing women that no-one’s ever heard of.”

As a country, the UK has a serious problem when it comes to highlighting senior women. There’s much discussion on how we encourage more women into senior roles, of whether we need quotas for the number of women on company boards and do women need to put themselves forward more. But what the media in particular is not good at is finding the women who are already there, who have made a name for themselves in their own sector but perhaps not outside of it. Maybe these women aren’t aware of the value they have?

Honey agrees, “I think all of the women are confident women but I think some of them don’t consider themselves to be someone who is leading their field. One woman kept saying, ‘Are you sure? Are you sure you want me?’. And I kept saying, ‘Yes, I’m sure,’ and her story is great and her picture is great and yes of course I wanted her.”

Enthusiasm and support radiates from Honey, you can see why people would want to be photographed by her. Like several of the women in her interviews she describes her career as a mix of luck and opportunity but her past work suggests it’s more than that, she’s obviously good at what she does but she’s also a regenerator. Someone who can move from one role to the next and throw herself into it.

She started her career in Bath making projects that she was personally passionate about, before moving to London and ending up in advertising. When the recession hit the work dried up and she found herself going back to her artistic roots, creating projects that met her own personal brief rather than that of an art director. She admits that everything she does has an element of the autobiographical in it but it also says something about the wider world and how women, in particular, see their place in it. She tells me about one project that captured young girls at home, at school, and dressed up as the one person they wished they could be. It’s this ability to capture human joy in both the mundane and the fantastical that comes across in 100 Leading Ladies, as well as the understanding that nobody can be defined by one aspect of their personalities, that we need to see the whole person.

She talks about one of her heroines, the photographer Eve Arnold and an interview she gave, “She wouldn’t talk about how she managed to be a famous photographer and have a child.” It was this reluctance to talk about work and family that Honey saw as the jumping-off point for the project. She wanted to create something which would inspire future career women and would show them story after story of women who’d made it and exactly how they’d done it.

It was particularly important that to her that the women were over 50. “That was my generation,” she says. “It’s the first generation that we can really look to as women working not just because they had to but because they had other motivations and ambition and a small space to try and do it.”

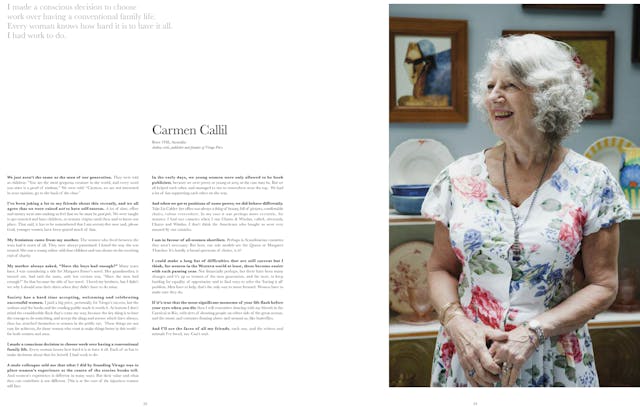

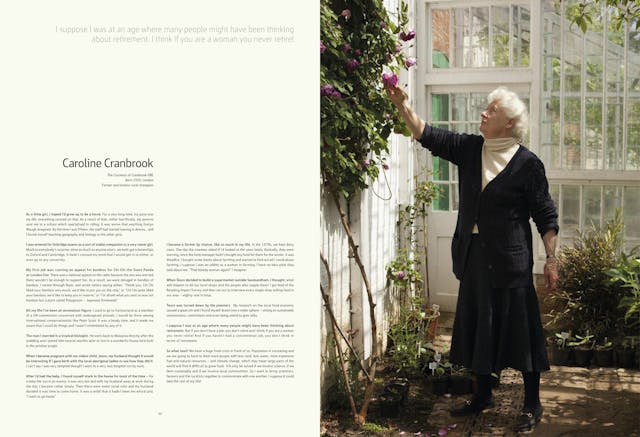

She feels hugely privileged that these women allowed her the access that they did, and that they were so honest with her. She asked each of them to choose the location of their portrait and the result is that each place tells you a little more about the woman photographed there.

“I loved that Martha Kearney chose the Chelsea Physic Garden and then Averil Mansfield, the first female professor of surgery, chose her favourite view in the Lake District which is near to where her home is now, it’s just this magical view. Loads chose their homes. To be invited in and see their homes and use those in the picture, that made a fabulous connection.”

100 Leading Ladies is a project powered by love and dedication but it’s been a long road from idea to activation. The photographs and interviews are all over and now Honey finds herself in a role she’s not used to, that of fundraiser. In a typically optimistic understatement she says that trying to secure funding has “rather taken the gloss off the fun” but she’s determined to do it.

“When it was the photography part of the process it was complicated but I knew how to do it because I’ve got a huge amount of experience. So I came to the end of the photographs and I thought, ‘Well now someone’s going to show me how to do fundraising’. Then I realised I was going to have to teach myself, which I did but it took a long time and was a huge learning curve.”

Looking around Honey’s home, seeing the packing boxes and bubble wrap, I don’t doubt for a second that she will make it happen. She’s a survivor who learns and adapts but more importantly puts her heart and soul into everything she does. So has it been worth it?

“Oh yes,” she says. “As long as people can see it.”